Bullet journals, zibaldoni, and commonplace books

The explosion of interest in bullet journals which I’ve spoken about before, shows no sign of slowing in 2017. The new year encourages many people to turn over a new leaf, and for many this means getting organised. The hundreds of beautifully decorated pages on #bulletjournal. I’ve said before, and I still agree, that it’s a bullet journal if you say it is, and it doesn’t have to fit someone else’s predefined idea. If the inventor welcomes lots of variations, then Sue on that bujo Facebook group you joined doesn’t get to say otherwise.

However, as I adapt my own bujo system, I find myself thinking of it in different terms. In my other life, I’m a historian, and so it won’t surprise anyone to hear that I tend to think about things in historical terms. A little bit of research reveals that there are some fascinating predecessors to the bullet journal, reaching as at least as far back as ancient Rome.

Bujos of the Past

Romans kept notes of ideas, maxims, quotations and so forth, and called these collections locus communis. Emperor Marcus Aurelius himself kept one, and it became his Meditations. From the third century, the Chinese kept biji, which were similarly collections of notes. These ancient practices led, eventually to the Italian zibaldone, which were the basis for commonplace books and later, bullet journals.

Zibaldoni

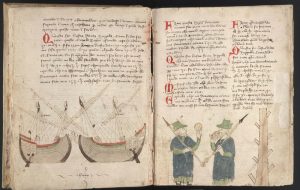

The genre really came into its own in the thirteenth century, when Venetian merchants started keeping notebooks with them on their travels and at home. They recorded their trading activities, but also notable events and experiences, in their zibaldoni (zee-bal-done-ee). Zibaldone (singular) means “heap of things” and indicates that these books were used as receptacles for any and all information and reminiscences that the author wanted to keep track of. An early example is the Zibaldone da Canal, dating to 1312.

Importantly, these books were written in the vernacular, meaning that they were for everyday use and not intended as formal documents (which would have been in Latin). In Florence, and other Italian cities, people kept ricordi (records), and libri segreti (secret, or private, books chiefly but not exclusively concerned with business information). In these books, people (almost always men) recorded business transactions, family births and deaths, observances of city life and political events technical information, indeed anything the author might want to refer to again later. Writers put these books together in no particular order, piling content in as and when it appeared. These books have provided highly important for historians. Giovanni di Paolo Rucellai, a fifteenth-century Florentine wool trader and statesman, was one of the most important keepers of a zibaldone. Not only does his book tell us about conducting business in the Renaissance, but it bears witness to the rise of the Medici and huge changes in civic government.

Commonplace Books

These Italian merchants brought their books to the foreign cities they traded with, and they caught on. By the eighteenth century, they were known in English-speaking countries as commonplace books, a translation of the Latin locis communis. Many notable people kept them: Thomas Jefferson, Jane Austen, H. P. Lovecraft and Napoleon, for example. A few have been published, like that of H. P. Lovecraft.

People filled their zibaldoni and commonplace books with all sorts of things: reflections on events, personal and political; recipes; business information; quotations; drawings and illustrations; letters; poems; reference tables, for example of weights and measures; proverbs and prayers.

Zibaldone Today

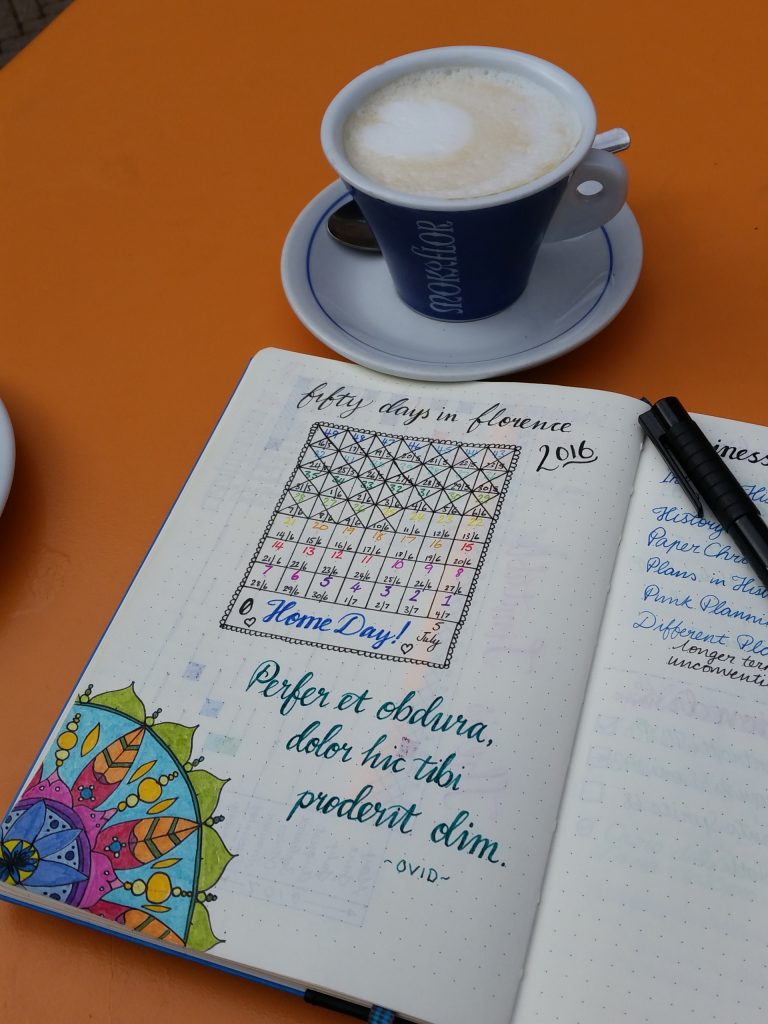

Today’s bujos record a huge variety of things. While I don’t usually track tv series I’m watching, I did track watching episodes of Murder One while I was doing archival work in Florence. Jane Austen may not have done this, but when we track and record things in our bujos, we’re taking part in a tradition that goes back far further than we tend to think.

Bullet journals, like zibaldoni and commonplace books are not diaries. They are not necessarily chronological, but they fulfil many of the functions of diaries. Like diaries, they work in two ways. They look both forwards (planned events and appointments) and backwards (when we record what actually happened). We keep track of our scheduled tasks and appointments in weekly or monthly spreads. We record things that happened without planning, in the form of general reflections or specific spreads. Gratitude logs are a popular way of marking things for which we were grateful each day. Historic zibaldoni and commonplace books tended to do much more reflection than planning, but the two are very much compatible. The bujo index helps out with locating information amid the hodgepodge.

I love the idea of renaming my bujo to acknowledge this long tradition. I kind of hate the abbreviation “bujo” anyway, even though I use it out of typing laziness. It seems increasingly fitting to me to think of my A5 dotted Leuchtturm1917 as a modern zibaldone (I study late medieval Italian history- I was hardly going to go for the English phrase!). I very much doubt it will ever of of as much interest to future generations of historians as that of Giovanni Rucellai. But that’s ok.